Canada Spiralling Out of Control, 4: Human Rights Legislation (1951-1954) and the End of “British Liberties”

Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV | Part V | Part VI | Part VII | Part VIII

The spiral was driven by a set of norms with an in-built radicalizing tendency. This tendency was contained in the supposition that the ethnic inequalities of the world, the wealth of European nations and the poverty of non-European nations, the impoverished status of blacks and aboriginals in the United States and the West generally, were a result of the discriminatory policies, the colonizing and under-developing activities of Europeans, rather than a result of cultural backwardness, differences in aptitudes or geographical lack of resources. If only all humans were granted the same rights to life, liberty, and economic success, the world could be improved drastically in a more egalitarian and prosperous direction.

Fair Employment and Fair Accommodation Practices Acts (1951-1954)

Beginning in the 1940s and through the 1950s, a growing network of groups, academics, media, ethnic associations, and trade unions, operating within a liberal atmosphere, and endorsing a pluralist view of politics, in which the state was seen as just one actor among many others engaged in politics, rather than as the actor in charge of ensuring the collective identity of the nation, pushed for “equal citizenship” and for legislation that would protect the “human rights” of citizens against discrimination. Basing themselves on the UN Charter declaration that every human should have equal rights “‘without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion,” the groups worked tirelessly in the late 1940s and early 1950s, with the Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Labor Committee playing the key roles, to bring legislation in Ontario, then in Canada generally, aimed at ending discrimination in employment, access to public spaces, housing and property ownership.

At first, in the early 1940s, the Canadian Jewish Congress was preoccupied with fighting domestic antisemitism and encouraging toleration and understanding between Jews and Christian groups. But after WWII, Jewish groups decided to go beyond fighting against the perception that they were unassimilable aliens, and instead designed a grand strategy against discrimination generally, through alliances with other liberal and minority organizations. With racism now tied to the actions of Nazis, these groups successfully instilled upon politicians, and the Canadian Anglo elite at large, the view that discriminatory practices were “fascist” and had no place in a liberal nation. By the early 1950s, these liberal groups managed to bring about the Fair Employment and Fair Accommodations Practices Acts (1951-1954), which declared Ontario’s allegiance to the principles of the UN Charter and the UN Declaration of Human Rights in rendering illegal any discrimination in employment and in access to public spaces in Ontario on grounds of race or creed.

These Acts, and other similar legislative measures, culminated, firstly, in the Canadian Bill of Rights enacted by Parliament on August 10, 1960, which is seen as the earliest expression of human rights law at the federal level, in declaring that all persons in Canada have “right to life, liberty and security.” Secondly, it culminated in the Ontario Human Rights Code, passed June 15, 1962, which prohibited discrimination on the grounds of race, ancestry colour, ethnic origin, creed, sexual orientation, age and family status.

The End of “British Liberties”

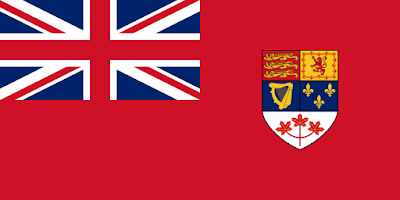

|

| Canadian Flag, 1922-1957 |

Now, while it can be reasonably argued that these human rights laws were within the bounds of classical liberal discourse in affording minorities the same legal status, in accordance with the principle that all citizens of a nation should be guaranteed equal rights in the eyes of the law, these acts and codes constituted a dramatic alteration in the traditional language of “British liberties” that had prevailed in Canada before WWII.

Before the Second World war, as Ross Lambertson has observed, “there was scant mention of human rights” not just in Canada but in international law. The idea behind the concept of human rights is that all humans enjoy equal natural rights by virtue of belonging to the human race, which is very different from the “British liberties” idea, which emphasizes one’s membership in a British national culture. These liberties included the principle of parliamentary supremacy, as the very keystone of the law and constitution, meaning that matters involving individual rights would be left to Parliament, which is to say that courts would defer to Parliament regarding issues about individual rights. (In Canada, be it noted, there was a plurality of parliaments within the federal-provincial division of powers).

The “British liberties” ensured by Parliament included such principles as fair play, which meant both fairness in the right of Canadian individuals to freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of religion, and in being treated equal under the law, “no man is above the law,” everyone is subject to the same laws. However, as has been argued by James Walker, such British liberties in Canada as freedom of speech and association “were interpreted to mean the right to declare prejudices openly, to refuse to associate with members of certain groups, including to hire them or to serve them.” Equality under the law did not mean that individuals were obligated to include within their free associations members regardless of race. Freedom of association was understood to include the right to discriminate on grounds of ethnicity, religion, and sex.

But I disagree with the standing argument that the human rights legislation constituted a break with libertarian liberalism, or classical liberalism. The standing argument says that Canadian liberalism before WWII emphasized individual freedoms rather than equal rights of citizenship. However, in my view, it was not simply that minorities were discriminated in their exclusion from restaurants, barber shops and many other public spaces. It was not simply, as Lambertson says, that the “ideal of freedom was accorded a higher importance than the ideal of equality” (p. 377). It was that the liberalism of this day was still ethnocentric, and this is why there were franchise laws that kept aboriginals in reserves and excluded them from the dominant British nation-state, as well as people of other races, through immigration laws that openly declared Asians and blacks to be unsuitable members of an official Canada intended to be British.

|

| Red Ensign, version 1957-1965 |

One does not have to agree with discriminatory measures to understand that it is wrong to project the libertarianism of today, devoid as it is of any appreciation for the importance of ethnic identity in its notion that we are all the same as individuals with rights, to understand that Canada’s emphasis on its British collective identity was crucial to the making of Canada, and that today Canada stands open to millions of immigrants encouraged to claim this nation as their own, and, therefore, encouraged to impose their own sense of the political, their ow collective tendencies upon a Eurocanadian people prohibited to have any collective identity.

The libertarianism of Canada before WWII, paradoxical as this may seem to us now, was collectivist in its belief that individual rights were rights which emerged from the British people, not from individuals as members of the human race, but from a particular British race, to which other ethnic groups that were White could assimilate but not people from very different races and cultures.

What made the acts and codes revolutionary was not simply that they were supportive of “equality of rights of minorities, at the expense of the libertarian rights of those wanting to exclude them” (p. 213). What made them revolutionary was that a new liberalism was being advocated in direct challenge to the ethnocentric liberalism that prevailed in the past, a more civic-oriented conception of the Canadian nation, based on universal values, was emerging wherein membership in the nation was defined purely in terms of values of equal rights rather than shared heritage, a common faith, and a common ethnic ancestry. The traditional ethnic nationalism of Canadians was being discredited as racist and illiberal.

In the degree to which this ethnic identity was de-legitimatized, the concept of the political in Canada would be weakened, with Canadians of British and European descent having less recourse to the older argument that it is perfectly within Canada’s political right to decide its ethno-cultural character. Indeed, these legislative changes, which I have only outlined, were the beginning of an accelerating spiral that would bring about ever more radical legislative changes, the end of all immigration restrictions by 1967, the complete redefinition of Canada as a multicultural nation in 1971, and much more.