A NATURAL HISTORY OF SPRING -

CAUTION:

POOR SLEDDING

"Spring is at hand. I take this early occasion to notify the public

of my opinion and to support it with collateral facts." - Stephen

Leacock

..

..

Under the entry heading "Canada", the 4th edition (1815)

Encyclopaedia Britannica offers this dreary caveat : "In Canada, the

spring, summer, and autumn are comprehended in five months, from May to

September. The rest of the year may be said to consist wholly of winter."

Presumably after that, immigration to Canada was restricted to those whose

hovel door had never been darkened by a set of encyclopaedias.

When March goes on forever And April's twice as long Who gives a damn

if spring has come As long as winter's gone.

In the 1530s, following Jacques Cartier's first voyage to the New World,

he brought back detailed accounts of the vegetative life he had seen in

the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. From 1610, when the first Jesuit missionary

arrived in Acadia, the order proved to be a gifted chronicler of the

nation-to-be.

For almost two centuries, their annual dispatches (known as the Jesuit

Relations) astonished Europeans with such New World oddities as sugar

producing

trees, riz sauvage, corn, squash and pumpkins. The Jesuits painstakingly

documented native agricultural practices, indigenous plants, and passed

along the ailmentary, medicinal, and ceremonial values ascribed to each.

Under their tutelage, aboriginals were released from the interminable

round

of camp relocation a slash-and-burn technology imposes. The Jesuits

subjected

Old World seeds to hardiness trials under New France's harsher conditions,

and propagated local varieties in special holding gardens to await

transportion

to France. So meticulous were these collections that when Jacques Philippe

Cornut published the first

Canadensium plantarum historia, 1635

Canadensium plantarum historia, 1635

Canadian botanical in 1635, he need hardly have misplaced his pince-nez.

Thanks to their efforts, M. Cornut was able to describe the subjects of

his Canadensium plantarum historia without troubling to venture anywhere

near Canada. The disproportionate number of North American wildflowers

classified today as "Canadense" or "Canadensis" stand

as an enduring tribute to Jesuit industry.

Robins follow the 35-degree isotherm north, because at 35 degrees

Fahrenheit,

earthworms reach the surface of the thawing ground.

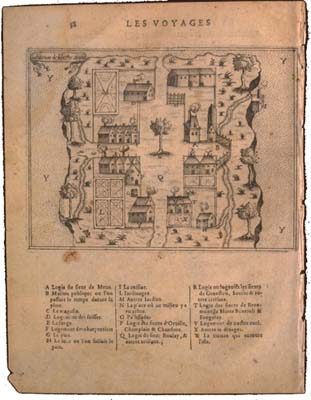

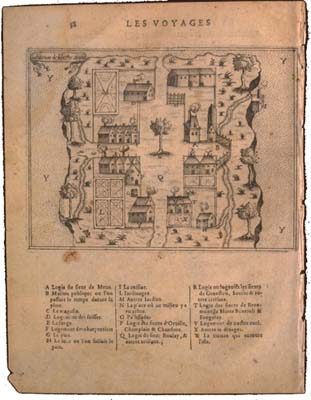

A map of Champlain's 1604 settlement at Isle Sainte-Croix on the Bay

of Fundy shows that

gardens were an immediate consideration. While that settlement failed,

his Quebec colony would boast a botanical garden. Canada's oldest

surviving

garden, the walled enclosure at St. Supician Seminary on Montreal's Notre

Dame Street, dates from the 1680s. By the 1670s, even the rude forts and

outposts of the Hudson's Bay Co. were planting English greens. Cape

Breton's

Fortress of Louisbourg 18th century formal potager gardens are still open

to the public.

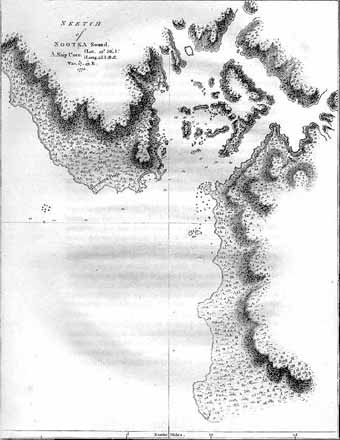

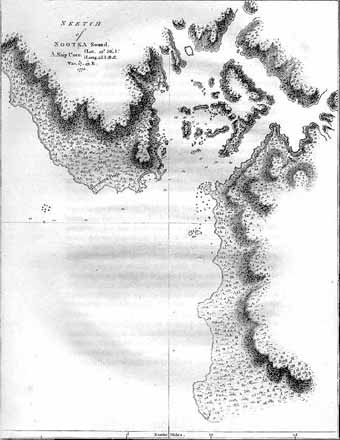

Maps of

the day depicted the bulk of the country as a great unmarked hinterland.

On British maps, this terra incognita terminated with New Albion (British

Columbia). Spain and Russia had poked about the area in a desultory kind

of way; but British ascendency was established in the spring of 1778 by

a man who had already made immense contributions elsewhere. Captain James

Cook came out of retirement to seek the fabled North-West passage. It was

to be his third, and fatal voyage. This venture brought together an

otherwise

familiar cast of historical figures. His midshipman was a 19-year-old

officer

cadet named George Vancouver; his sailing master a 21-year-old

perfectionist

named William Bligh. As the young Cook had in his day charted the

Newfoundland

coastline, so Bligh charted - accurately - the Alaskan waters where the

Exxon Valdez was to run aground 200 years later.

Maps of

the day depicted the bulk of the country as a great unmarked hinterland.

On British maps, this terra incognita terminated with New Albion (British

Columbia). Spain and Russia had poked about the area in a desultory kind

of way; but British ascendency was established in the spring of 1778 by

a man who had already made immense contributions elsewhere. Captain James

Cook came out of retirement to seek the fabled North-West passage. It was

to be his third, and fatal voyage. This venture brought together an

otherwise

familiar cast of historical figures. His midshipman was a 19-year-old

officer

cadet named George Vancouver; his sailing master a 21-year-old

perfectionist

named William Bligh. As the young Cook had in his day charted the

Newfoundland

coastline, so Bligh charted - accurately - the Alaskan waters where the

Exxon Valdez was to run aground 200 years later.

Resolution and Discovery at Nootka Sound During his first

voyage to the South Seas,

Cook's scientific team had collected 30,000 specimens.

Resolution and Discovery at Nootka Sound During his first

voyage to the South Seas,

Cook's scientific team had collected 30,000 specimens.

The effect of introducing 1,400 entirely new plant species to a world

where only 6,000 had previously been known was to accelerate knowledge

of the natural world by 25 per cent in just three years. That deluge of

information almost certainly contributed to the formulation of Thomas

Malthus'

1798 theories, which in turn inspired Charles Darwin. The chief botanist

on Cook's first voyage -- Joseph Banks -- typified the spirit of his

times.

While he was certainly driven by scientific curiousity, Banks proved an

equally tireless promoter of commercial applications for these newly

described

botanicals. Men like Banks and Cook represented the best European spirit

Joseph Banks

Joseph Banks

during the great exploration: curious, courageous, enterprising and

inventive. As a member of the Royal Society, Banks had the requisite clout

to not only introduce tea as a cash crop to India, but to commission HMS

Bounty to transport breadfruit for cultivation from Tahiti to the West

Indies. In a further twist of fate, it was Banks again who had recognized

Australia's potential as a great open-air prison. He presented a paper

to Parliament outlining his ideas in some detail. Following the mutiny

on the breadfuit-laden Bounty, the same William Bligh was appointed

governor

to the fledgling New South Wales penal colony. He held the post for three

years -- and then his prisoners mutinied.

No wonder a mother bear with cubs is dangerous. She gives birth during

deepest hibernation and wakes to find that she has been feeding voracious

offspring ever since.

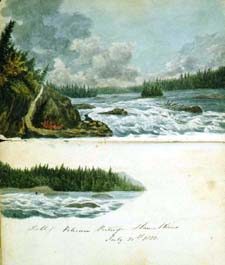

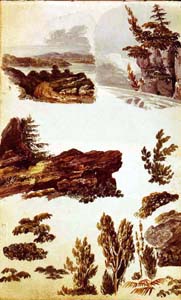

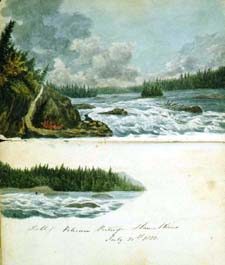

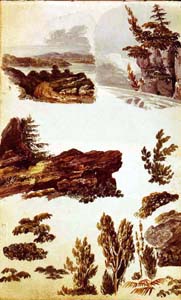

Under gruelling

conditions, New World plants were constantly being catalogued, collected,

and laboriously transported back to England. In February of 1825,

following

an eight month voyage out, David Douglas found himself deposited at the

mouth of the Columbia River. The Royal Horticultural Society had been well

advised to place their trust in the indomitable Mr. Douglas. He would

prove

very much equal to the task of examining the area supporting the most

living

matter per hectare in the world -- New Albion's coastal rain forest. When

he started back on March 20, 1827, he chose an overland route that took

him by foot over the Rocky Mountains, and from there via canoe, to York

Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Incredibly, when he left for

England

on October 11, both he and his plant specimens were still alive. Known

to us for his "Douglas" fir, it was his introduction of the flowering

currant that more than subsidized the entire expedition. Douglas was to

meet an untimely end on the same Hawaiian island that had claimed the life

of Captain Cook.

Under gruelling

conditions, New World plants were constantly being catalogued, collected,

and laboriously transported back to England. In February of 1825,

following

an eight month voyage out, David Douglas found himself deposited at the

mouth of the Columbia River. The Royal Horticultural Society had been well

advised to place their trust in the indomitable Mr. Douglas. He would

prove

very much equal to the task of examining the area supporting the most

living

matter per hectare in the world -- New Albion's coastal rain forest. When

he started back on March 20, 1827, he chose an overland route that took

him by foot over the Rocky Mountains, and from there via canoe, to York

Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Incredibly, when he left for

England

on October 11, both he and his plant specimens were still alive. Known

to us for his "Douglas" fir, it was his introduction of the flowering

currant that more than subsidized the entire expedition. Douglas was to

meet an untimely end on the same Hawaiian island that had claimed the life

of Captain Cook.

Captain Cook

Captain Cook

"In the evenings we wandered through the woodland paths, beneathe

the glowing Canadian sunset, and gathered rare specimens of of strange

plants and flowers. Every object that met my eyes was new to me, and

produced

that peculiar excitement which has its origin in a thirst for knowledge

and a love of variety." (Susanna Moodie, 1832)

Of the 4,200

plant species growing in Canada today, only about 1,000 have been

introduced.

As the nation was settled, Canada continued to produce an improbable

number

of people eager to inventory our wealth of coastal, alpine, prairie,

woodland,

maritime and Arctic plants.

Of the 4,200

plant species growing in Canada today, only about 1,000 have been

introduced.

As the nation was settled, Canada continued to produce an improbable

number

of people eager to inventory our wealth of coastal, alpine, prairie,

woodland,

maritime and Arctic plants.

With few exceptions, when Europeans settled here, it was for life.

The seeds they brought with them nourished spiritual as much as physical

needs. Pioneer gardens quickly grew into living reminders of a world that

was lost to them forever. Among rose growing circles, there is a famous

story of a woman who had emigrated out from G ermany

with a cherished piece of rootstock from her mother's favourite rambling

rose. That annual concussion of colour and fragrance must

have served as a continual reproach, for while the cutting survived the

journey, two of her children had not. Her experience tends to put the

"anguish"

of contributing to your own language training (which some current

newcomers

allegedly feel) into the appropriate fiscal context.

ermany

with a cherished piece of rootstock from her mother's favourite rambling

rose. That annual concussion of colour and fragrance must

have served as a continual reproach, for while the cutting survived the

journey, two of her children had not. Her experience tends to put the

"anguish"

of contributing to your own language training (which some current

newcomers

allegedly feel) into the appropriate fiscal context.

"Our woods and clearings are now full of beautiful flowers. ...

You will recognize among them many of the cherished pets of our gardens

and green-houses, which are here flung carelessly from Nature's lavish

hand among our woods and wilds." (Catherine Parr-Traill, 1834)

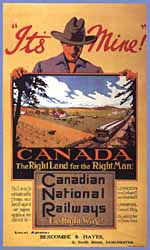

Toward the end of the 1800s, a new sense of social responsibility was

evolving. Known as the "social gospel", people came to the (now

improbable) conclusion that benefit without contribution was unseemly

evidence

of greed. Into this fertile ground, two uniquely Canadian seeds

germinated.

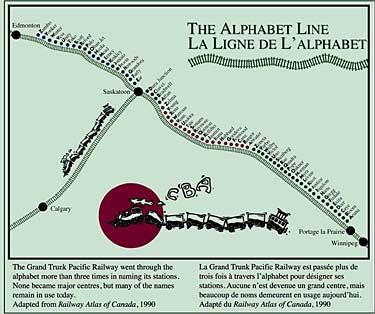

Just as the British East India Company and Joseph Banks had pursued the

twin aims of pure knowledge and "impure" commerce, two of Canada's

biggest corporations would underwrite remarkable agricultural programmes.

At that time, both Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railways

were waging aggressive recruitment campaigns to entice Europeans to settle

in rural Canada. In the case of CP, their "Railway Station Program"

-- meant to beautify unlovely prairie whistle-stops -- started modestly

enough. Then, to identify ideal local cultivars, a series of experimental

farms were established in 1884. The idea fostered goodwill and

agricultural

productivity while not inconsequentially, boosting economic growth along

CP's lines. CP freely acknowledged its motives -- good farms meant good

business. These experimental farms gradually came to encompass mixed

farming

-- even hothouse flowers -- cleverly destined for use in CP's own trains

and hotels. "Better Farming" trains began to slowly ply the prairies,

bringing lecturers and up to the minute agricultural thinking to capacity

crowds throughout isolated communities. The idea was so successful that

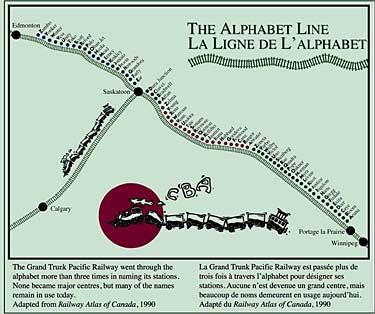

CN, Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk Pacific  Railway

jumped on board. In addition to simple grain and weed information, the

teaching trains were soon shunting around blue-ribbon livestock and

poultry.

CP president Sir William Van Horne pioneered a programme of "lending

out" prize boars and bulls to improve local livestock strains -- with

the single proviso that every farm in the community must have equal access

to the stud. All aspects of rural life were represented on the

agricultural

trains: dairy, machinery, outbuildings, home economics, child care, boys

& girls magic lantern shows, tree planting, forage crops, vegetable

gardening, beneficial insects, drainage, textiles, bee-keeping, orchards,

soil conservation -- with soil analysis performed on the spot. The better

farming trains promoted innovations like irrigation, refrigeration, and

Mr. Marconi's radio. CN introduced mail-order agricultural extension

courses.

Meanwhile, those mock-Tudor CPR stations were lovingly landscaped within

an inch of their lives - intially to demonstrate how the region could

bloom

- but, finally, in a spirit of fierce competition. Thirty-eight years

after

the program's inception, the Canadian Pacific Staff Bulletin (July 1946)

acknowledged "over 1,250 employees who voluntarily maintain gardens

on Company property. To them some 10,000 packets of seeds are sent out

each season." In most areas, these enthusiastic railway initiatives

would pave the way for later university and government experimental farms,

extension departments, horticultural societies and garden clubs. It was

a remarkable contribution -- and in typical Canadian fashion -- now

utterly

forgotten.

Railway

jumped on board. In addition to simple grain and weed information, the

teaching trains were soon shunting around blue-ribbon livestock and

poultry.

CP president Sir William Van Horne pioneered a programme of "lending

out" prize boars and bulls to improve local livestock strains -- with

the single proviso that every farm in the community must have equal access

to the stud. All aspects of rural life were represented on the

agricultural

trains: dairy, machinery, outbuildings, home economics, child care, boys

& girls magic lantern shows, tree planting, forage crops, vegetable

gardening, beneficial insects, drainage, textiles, bee-keeping, orchards,

soil conservation -- with soil analysis performed on the spot. The better

farming trains promoted innovations like irrigation, refrigeration, and

Mr. Marconi's radio. CN introduced mail-order agricultural extension

courses.

Meanwhile, those mock-Tudor CPR stations were lovingly landscaped within

an inch of their lives - intially to demonstrate how the region could

bloom

- but, finally, in a spirit of fierce competition. Thirty-eight years

after

the program's inception, the Canadian Pacific Staff Bulletin (July 1946)

acknowledged "over 1,250 employees who voluntarily maintain gardens

on Company property. To them some 10,000 packets of seeds are sent out

each season." In most areas, these enthusiastic railway initiatives

would pave the way for later university and government experimental farms,

extension departments, horticultural societies and garden clubs. It was

a remarkable contribution -- and in typical Canadian fashion -- now

utterly

forgotten.

Govt of Canada publication, 1930

The Macdonald Movement in Canada, 1910

At the same time, this notion of making "better farmers"

prompted Sir William MacDonald (yes, the tobacco MacDonalds) and education

reformer James Wilson Robertson, to conceive the school gardening and

agricultural

program that came to be known as the "MacDonald Movement". "In

the two new provinces [Alberta and Saskatchewan], the number of schools

has increased from 75 in 1886 to 845 in 1904." (The Canadian West,

1904) One of the drawbacks of the teaching trains was that with very few

exceptions, information was imparted only in English. A variety of

European

immigrants had come to farm what was then a genuinely enormous country:

the challenge was not just to "channel" agricultural information

from child to parent, but to inspire the next generation to gladly stay

on magnificently productive farms. As an auxillary, the curriculum

acculturated

children, taught Canadian standards of good citizenship, and inculcated

all but forgotten virtues like self-sufficiency, individualism, and pride

in ownership.

L'Agriculture à l'école primaire, 1925

L'Agriculture à l'école primaire, 1925

While the teaching trains mostly concentrated on the prairie regions,

the school program really came into its own in Ontario and the Maritimes

(though there was a great deal of crossover both ways). "In 1906,

in Carleton County, in schools without gardens 49 per cent of the

candidates

passed, while those who came from the five schools to which were attached

gardens 71 per cent were successful. Apparently the work with the hands

in the garden increased the capacity for work with books." (John W.

Chalmers, Schools of the Foothills Province: The Story of Public Education

in Alberta, 1967) In fact, nearly everyone was more enthusiastic than

school

Inspector M. E. LaZerte: ‘There are too many cases where the little mound

of earth serves to mark the grave of the seed or of the early-departed

plant.' What is of particular interest is this persistant ability to take

the long view. From Cook's voyages to these rural agricultural

innovations,

what really seemed to fire men's imaginations was the prospect of taking

a hand in an improved future -- another all but forgotten virtue.

It might be worthwhile to ask: Whatever happened to us? How could such

ambitious projects succeed in an underdeveloped and geographically

isolated

nation? Certainly there was the key individual and his vision, but in the

face of overwhelming response, these projects took on a life of their own.

Notice that no one seemed to get trampled by "dangerous" enthusiasms.

On the contrary, when Laurier pronounced the 20th century Canada's

century,

he had a per capita annual growth rate of 4.2% GDP (in real, inflation

adjusted terms) between 1896 and 1913 to back him up. By the time the

Second

World War rolled around, something had happened to Canada. Consider: when

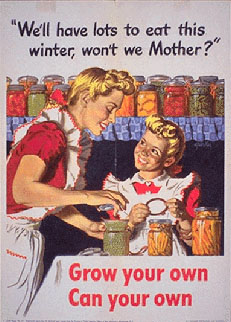

we launched our war effort in 1939, "official" sanction for Victory

Gardens was not to be forthcoming until 1943. Throughout the war years,

the Victory Garden defined the "home" experience for millions

of Britons, Australians and New Zealanders. After the Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbour, Americans immediately put front yards, vacant lots and

public

lands under the plough.

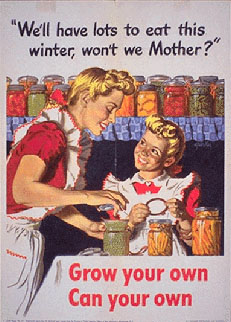

US Victory Garden Programme

US Victory Garden Programme

In a 1942 pamphlet, the Ontario Department of Agriculture fusses:

"Unless

conditions are favourable, a vegetable garden should not be undertaken.

We cannot afford to waste seed, fertilizer, equipment and energy unless

location and soil are suitable and the gardener is determined to follow

through to harvest and use." This showed a peculiar absence of confidence

in a population that was then, largely farm-raised.

A 1942 federal Dept. of Agriculture brochure maintains the finger

wagging:

"Q: Could I help the war effort by planting a vegetable garden? A:

If you have not had one before, and have not had previous experience, it

is not urged that you plant one this year." No other nation so nearly

equated a vegetable garden with top secret rocketry. When did this

official

view of Canadians as hopelessly inept bunglers gain such wide currency?

By 1943, when Ottawa had relented, year's end newspapers reported that

209,200 Victory Gardens were producing an average 550 lbs of vegetables

each.

Into the dark of January the seed catalogue bloomed - Robert Kroetsch

The range and diversity of plant life in late Victorian seed catalogues

was immense. To name just a few, over 150 varieties of asters, thirty or

forty nasturtiums and fifty annual phlox were on offer. A turn of the

century

census of Canadian apples lists over one hundred commonly grown varieties.

Today, we grow about half a dozen. Our forefathers grew beans that lazily

ripened on and off over the course of a growing season. People picked the

amount of beans they needed for dinner, and if they tasted good, who would

have known or cared, that they didn't "keep" or "ship"?

Again, what happened? Over the years, seedmen have bred and hybridized

beans and everything else, with large commercial growers in mind. Now,

unless you buy a "heritage variety", your plant will deliver

"desirable" keeping, shipping and ripening characteristics, often

at the expense of flavour. Worse, Monsanto has patented the so-called

"Terminator

Gene" which renders all seed (except theirs) infertile. It might be

time for Canadians to begin asking themselves whether, for the sake of

"convenience" or "niceness", we are voluntarily restricting

genuine diversity to produce a nation of simpering winter tomatoes --

outwardly

unique, but inwardly bland and lifeless. In short: without a single

redeeming

flaw.

Neither fish nor fowl; building the "better" Canadian

Neither fish nor fowl; building the "better" Canadian

Seemingly, we are not even optimistic enough to obey the first

imperative

of all living beings. According to the Toronto Sun (Feb. 5, 1999), Quebec

in 1997 achieved a China-like birth rate "of 1.5 children per woman

of childbearing age. ... [In 1996, among newborns] the most common surname

on the island of Montreal was Nguyen, of Vietnamese origin. ... Runner

up to Nguyen, by the way, was Patel, of East Indian vintage." What

happened? In the mid-1700s, Quebec's birthrate was a staggering 65.2 per

1000 population and families of fifteen children were commonplace. Was

it the maypole?

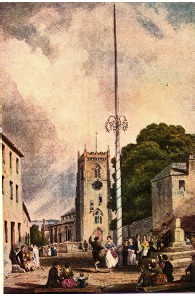

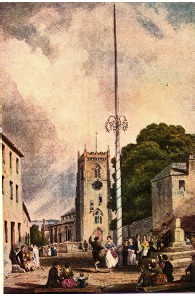

"On the first of May each year, the winter snows forgotten, the

habitants arrived at the manoir in their best clothes, the youths bearing

a tall fir with branches and bark stripped to within a few feet of the

tip. This was dug in before the house, and embellished with strings and

ribbons. The seigneur and his family came out to sit in chairs and applaud

as couples kicked up their heels, dancing around the maypole. Flasks of

liquor were passed, and fusillades of blank cartridges, hand-packed for

the occasion, roared from the bushes. All were invited into the

stone-built

manoir where food was laid out on long tables. The seigneur tapped the

brandy cask and the censitaires rushed outside to blast away at the fir

pole until it was blackened with powder burns.." (Leslie Hannon, Redcoats

and Loyalists, 1978)

Somehow it seems appropriate that our Mayday! distress signal comes

from M'aidez! (help me) in French. While it's perplexing to think that

the Christian church appropriated so many old European holidays, it is

beyond grotesque to consider that (for most of the 20th century) the

sweetest

day of the old calendar has been the exclusive preserve of stolid,

ashen-faced

party bosses in size 54-short suits.

The first evidence of a Communist affinity for May first emerged during

that mass bloodletting of the French Revolution known as the Terror; when

ominous revolutionary maypoles (Mai Sauvage) dotted the landscape of rural

France. The message, then as now, was unmistakable: "Come, join us,

or we'll destroy you". Nothing could be further from the spirit of

mayday as it was (and often still is) celebrated in France, Spain, the

United Kingdom, the Low Countries, Germany and Scandinavia. Records of

Roman Maytime dances and processions to Floralia, the Goddess of flowers

and Spring are confidently dated to 258 BC. To the Celts, Beltaine (or

mayday) was the counterpoint to Samhain.

Oh, do not tell the Priest our plight, Or he would call it a sin; But

we have been out in the woods all night, A-conjuring Summer in! - Rudyard

Kipling, A Tree Song

From time immemorial, on the night of April 30 (now officially income

tax night) young people left their European towns and villages and went

into the fields and forests to "bring in the May". The young

women gathered flowers to bedeck themselves, their families, and their

homes, while the young men selected and cut a slender young fir sapling

full of the fertile energy of the green wood. It was, after all, a

fertility

rite, and there was always a spike of births the following January to

prove

it. Once the young men and women had collected themselves, they made a

merry procession back, stopping at each home to leave some flowers, and

receive some food and drink. On the village green, the tree was stripped

of all its branches save the crown of foliage. The maypole might be hung

with guild signs, and village exploits might be carved in the trunk in

a totemic way; but it was always decked out with herbs, flowers, ribbons

and greenery near the top.

The Queen of May and her retinue of men dressed as stags or bears,

the Lord of the May, or Jack-in-the-Green performed, and there were manly

games of strength to celebrate the God coming into his prime. Finally,

the revellers danced on the village green. Intricate plaiting designs

(barber's

pole, spider's web, Gypsy's tent) emerged from the interweaving of the

dancers and their ribbons.

There were an infinite number of Maytime variations; throughout the

length and breadth of Europe girls washed their faces in May morning dew

to stay beautiful through the year. In Switzerland the young men cut small

pine trees, called Maitannli, which they decorated and planted before the

homes of girls they admired. Only girls of good character received the

Maitannli; the looser sort might waken on mayday morning to find a

grotesque

straw puppet outside the window.

The Roman Church proved surprisingly tolerant of May festivities, going

so far as to make a tradition of crowning statues of Mary with flowers

on mayday (she too, is called the Queen of the May). The Puritans, on the

other hand, hardly knew what to despise most: the drinking - the dancing

- the debauchery? In his 1583 "Anatomie of Abuses", Phillip Stubbes

anticipated Freud by many centuries as he railed against the abomination

of the maypole: "They have twentie or fortie yoke of oxen, every oxe

having a sweet nose-gay of flowers placed on the tip of his hornes, and

these oxen drawe home this May-Pole (this stinking idol, rather), which

is covered all over with floures and hearbs, bound round about with

strings,

from the top to the bottome, and sometime painted with variable coulours,

with two or three hundred men, women and children following it with great

devotion. And this being reared up ... then fall they to daunce about it,

like as the heathen people did at the dedication of the Idols, wereof this

is a perfect pattern, or rather the thing itself. I have heard it credibly

reported (and that viva voce) by men of great gravitie and reputation,

that of forty, threescore, or a hundred maides going to the wood

over-night,

there have scarcely the third of them returned home againe undefiled."

In 1644, an obliging Parliament banned the maypole.

The Witch Trial

The Witch Trial

If he danced, it was round the whipping-post, which might be termed

the Puritan Maypole. Nathaniel Hawthorne

When Charles II was restored to the throne a few years later, a handsome

134 foot maypole was promptly erected in London. It had long been the

practice

to advertise a daughter's betrothal with a maypole outside the home, but

maypoles sprung up spontaneously across the country as a sign of loyalty

to the crown. By 1660, mayday celebrations were again the norm. It is

significant

that for all the fanatical denunciation, Puritan persecutions never

seriously

threatened the maypole. An emerging belief system would (briefly) relegate

self-important intolerance to its proper corner, but it would, at the same

time, deprive agriculture and fertility of much of the ancient attendant

mystery. It is ironic that as the scientific method gained supremacy, it

achieved in a routine, passionless way, what repression had not.

In 1713, a

bright new maypole was installed opposite London's Somerset House. "This

second May-pole had two gilt balls and a vane on its summit. On holidays

the pole was decorated with flags and garlands. It was removed in 1718,

and sent by Sir Isaac Newton to Wanstead Park to support the largest

telescope

in Europe." (The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E. Cobham Brewer,

1894) The final coup de grace came when the Victorians revived the maypole

tradition as a "rustic delight". Far from the potent fertility

symbol presiding over drunken men dressed as stags pursuing screaming

maidens,

the poor, emasculated maypole was finally reduced to a pretty prop in

children's

dancing games.

In 1713, a

bright new maypole was installed opposite London's Somerset House. "This

second May-pole had two gilt balls and a vane on its summit. On holidays

the pole was decorated with flags and garlands. It was removed in 1718,

and sent by Sir Isaac Newton to Wanstead Park to support the largest

telescope

in Europe." (The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E. Cobham Brewer,

1894) The final coup de grace came when the Victorians revived the maypole

tradition as a "rustic delight". Far from the potent fertility

symbol presiding over drunken men dressed as stags pursuing screaming

maidens,

the poor, emasculated maypole was finally reduced to a pretty prop in

children's

dancing games.

Down nearly to the ground the pole was dressed with birchen boughs,

and others of the liveliest green, and some with silvery leaves, fastened

by ribbons that fluttered in fantastic knots of twenty different colors,

but no sad ones. Garden flowers, and blossoms of the wilderness, laughed

gladly forth amid the verdure, so fresh and dewy that they must have grown

by magic on that happy pine-tree. (The May-Pole of Merry Mount, Nathaniel

Hawthorne)

"When winter comes, spring can be a lot farther behind in some

places than in others. At the southerly limit of the Great Lakes system,

on the shore of Lake Erie, the growing season - from the last frost of

spring to the first frost of autumn - usually lasts about 200 days.

Because

of the earth's tilt, sunlight strikes the fields here longer and more

directly

on a fine day in April than it does on the same day toward the more

northerly

limit of the same water system, in the St. Lawrence valley. Here the

growing

season shrinks to about 150 days. (The yellow-hearted violet called

Canadensis

blossoms almost a month later in Edmonton than it does near Niagara).

North

of the Arctic Circle spring doesn't arrive until the end of May and the

growing season doesn't last much more than 50 days. They're long days,

though, many of them with more than 20 hours of sunshine. Species that

do survive here can get through in weeks the stages of living that take

more southerly specimens months." (The Sexual Imperative, Ken Lefolii)

On the voyage to America 12 children were born,

of which all but one died. Of the above 262 souls embarked, 53 died on

the ocean and the remaining 221 landed safely at Halifax. There were 183

freights and 53 bedplaces. From the 8th of July 1752 to the 28th of

February

1753, 83 persons from the above-mentioned ship died in Halifax. We were

14 days travelling down the Rhine and 14 weeks on the ocean, not counting

the time we were on board the ship in Rotterdam and again in Halifax

before

we were put to ashore, all of which amounted to 22 weeks. - Excerpt from

Johann Michael Schmitt's Bible, as translated by Winthrop Bell.

A "freight" was a full-fare passenger - everyone over a certain

stipulated age, which varied from time to time or ship to ship, but was

frequently 14 years. Infants (usually under the age of 4) were carried

free and no space allocation was made for them. Children between those

ages were accounted "half-freights." Thus: Mr Schmitt meant by

the numbers of adults and of children (on the GALE from Rotterdam leaving

Leymen for America on 9 May 1752 and docking in Halifax on 8 June 1752)

were such that the 262 "souls" amounted to 183 "freights".

The still extant ship's manifest shows that there were actually 249

"souls"

and 183 "freights". The "bedplaces" were subdivisions

of the 'tween decks space in the ship, to which the emigrants were

assigned.

There were certain regulations with respect to these. The minimum

"bedplace"

size was supposed to be 6 feet square, and no more than 4 "freights"

were to be assigned to any one "bedplace." On John Dick's ships

the "bedplace" sizes were somewhat larger than the legal minimum.

Mr. Schmitt's statement means that the GALE's emigrants had somewhat more

room than they would have had the ship been filled. - Lunenberg County,

Nova Scotia genealogy discussion list

..

..

Maps of

the day depicted the bulk of the country as a great unmarked hinterland.

On British maps, this terra incognita terminated with New Albion (British

Columbia). Spain and Russia had poked about the area in a desultory kind

of way; but British ascendency was established in the spring of 1778 by

a man who had already made immense contributions elsewhere. Captain James

Cook came out of retirement to seek the fabled North-West passage. It was

to be his third, and fatal voyage. This venture brought together an

otherwise

familiar cast of historical figures. His midshipman was a 19-year-old

officer

cadet named George Vancouver; his sailing master a 21-year-old

perfectionist

named William Bligh. As the young Cook had in his day charted the

Newfoundland

coastline, so Bligh charted - accurately - the Alaskan waters where the

Exxon Valdez was to run aground 200 years later.

Maps of

the day depicted the bulk of the country as a great unmarked hinterland.

On British maps, this terra incognita terminated with New Albion (British

Columbia). Spain and Russia had poked about the area in a desultory kind

of way; but British ascendency was established in the spring of 1778 by

a man who had already made immense contributions elsewhere. Captain James

Cook came out of retirement to seek the fabled North-West passage. It was

to be his third, and fatal voyage. This venture brought together an

otherwise

familiar cast of historical figures. His midshipman was a 19-year-old

officer

cadet named George Vancouver; his sailing master a 21-year-old

perfectionist

named William Bligh. As the young Cook had in his day charted the

Newfoundland

coastline, so Bligh charted - accurately - the Alaskan waters where the

Exxon Valdez was to run aground 200 years later.

Under gruelling

conditions, New World plants were constantly being catalogued, collected,

and laboriously transported back to England. In February of 1825,

following

an eight month voyage out, David Douglas found himself deposited at the

mouth of the Columbia River. The Royal Horticultural Society had been well

advised to place their trust in the indomitable Mr. Douglas. He would

prove

very much equal to the task of examining the area supporting the most

living

matter per hectare in the world -- New Albion's coastal rain forest. When

he started back on March 20, 1827, he chose an overland route that took

him by foot over the Rocky Mountains, and from there via canoe, to York

Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Incredibly, when he left for

England

on October 11, both he and his plant specimens were still alive. Known

to us for his "Douglas" fir, it was his introduction of the flowering

currant that more than subsidized the entire expedition. Douglas was to

meet an untimely end on the same Hawaiian island that had claimed the life

of Captain Cook.

Under gruelling

conditions, New World plants were constantly being catalogued, collected,

and laboriously transported back to England. In February of 1825,

following

an eight month voyage out, David Douglas found himself deposited at the

mouth of the Columbia River. The Royal Horticultural Society had been well

advised to place their trust in the indomitable Mr. Douglas. He would

prove

very much equal to the task of examining the area supporting the most

living

matter per hectare in the world -- New Albion's coastal rain forest. When

he started back on March 20, 1827, he chose an overland route that took

him by foot over the Rocky Mountains, and from there via canoe, to York

Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Incredibly, when he left for

England

on October 11, both he and his plant specimens were still alive. Known

to us for his "Douglas" fir, it was his introduction of the flowering

currant that more than subsidized the entire expedition. Douglas was to

meet an untimely end on the same Hawaiian island that had claimed the life

of Captain Cook.

Of the 4,200

plant species growing in Canada today, only about 1,000 have been

introduced.

As the nation was settled, Canada continued to produce an improbable

number

of people eager to inventory our wealth of coastal, alpine, prairie,

woodland,

maritime and Arctic plants.

Of the 4,200

plant species growing in Canada today, only about 1,000 have been

introduced.

As the nation was settled, Canada continued to produce an improbable

number

of people eager to inventory our wealth of coastal, alpine, prairie,

woodland,

maritime and Arctic plants.  ermany

with a cherished piece of rootstock from her mother's favourite rambling

rose. That annual concussion of colour and fragrance must

have served as a continual reproach, for while the cutting survived the

journey, two of her children had not. Her experience tends to put the

"anguish"

of contributing to your own language training (which some current

newcomers

allegedly feel) into the appropriate fiscal context.

ermany

with a cherished piece of rootstock from her mother's favourite rambling

rose. That annual concussion of colour and fragrance must

have served as a continual reproach, for while the cutting survived the

journey, two of her children had not. Her experience tends to put the

"anguish"

of contributing to your own language training (which some current

newcomers

allegedly feel) into the appropriate fiscal context.

Railway

jumped on board. In addition to simple grain and weed information, the

teaching trains were soon shunting around blue-ribbon livestock and

poultry.

CP president Sir William Van Horne pioneered a programme of "lending

out" prize boars and bulls to improve local livestock strains -- with

the single proviso that every farm in the community must have equal access

to the stud. All aspects of rural life were represented on the

agricultural

trains: dairy, machinery, outbuildings, home economics, child care, boys

& girls magic lantern shows, tree planting, forage crops, vegetable

gardening, beneficial insects, drainage, textiles, bee-keeping, orchards,

soil conservation -- with soil analysis performed on the spot. The better

farming trains promoted innovations like irrigation, refrigeration, and

Mr. Marconi's radio. CN introduced mail-order agricultural extension

courses.

Meanwhile, those mock-Tudor CPR stations were lovingly landscaped within

an inch of their lives - intially to demonstrate how the region could

bloom

- but, finally, in a spirit of fierce competition. Thirty-eight years

after

the program's inception, the Canadian Pacific Staff Bulletin (July 1946)

acknowledged "over 1,250 employees who voluntarily maintain gardens

on Company property. To them some 10,000 packets of seeds are sent out

each season." In most areas, these enthusiastic railway initiatives

would pave the way for later university and government experimental farms,

extension departments, horticultural societies and garden clubs. It was

a remarkable contribution -- and in typical Canadian fashion -- now

utterly

forgotten.

Railway

jumped on board. In addition to simple grain and weed information, the

teaching trains were soon shunting around blue-ribbon livestock and

poultry.

CP president Sir William Van Horne pioneered a programme of "lending

out" prize boars and bulls to improve local livestock strains -- with

the single proviso that every farm in the community must have equal access

to the stud. All aspects of rural life were represented on the

agricultural

trains: dairy, machinery, outbuildings, home economics, child care, boys

& girls magic lantern shows, tree planting, forage crops, vegetable

gardening, beneficial insects, drainage, textiles, bee-keeping, orchards,

soil conservation -- with soil analysis performed on the spot. The better

farming trains promoted innovations like irrigation, refrigeration, and

Mr. Marconi's radio. CN introduced mail-order agricultural extension

courses.

Meanwhile, those mock-Tudor CPR stations were lovingly landscaped within

an inch of their lives - intially to demonstrate how the region could

bloom

- but, finally, in a spirit of fierce competition. Thirty-eight years

after

the program's inception, the Canadian Pacific Staff Bulletin (July 1946)

acknowledged "over 1,250 employees who voluntarily maintain gardens

on Company property. To them some 10,000 packets of seeds are sent out

each season." In most areas, these enthusiastic railway initiatives

would pave the way for later university and government experimental farms,

extension departments, horticultural societies and garden clubs. It was

a remarkable contribution -- and in typical Canadian fashion -- now

utterly

forgotten.

In 1713, a

bright new maypole was installed opposite London's Somerset House. "This

second May-pole had two gilt balls and a vane on its summit. On holidays

the pole was decorated with flags and garlands. It was removed in 1718,

and sent by Sir Isaac Newton to Wanstead Park to support the largest

telescope

in Europe." (The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E. Cobham Brewer,

1894) The final coup de grace came when the Victorians revived the maypole

tradition as a "rustic delight". Far from the potent fertility

symbol presiding over drunken men dressed as stags pursuing screaming

maidens,

the poor, emasculated maypole was finally reduced to a pretty prop in

children's

dancing games.

In 1713, a

bright new maypole was installed opposite London's Somerset House. "This

second May-pole had two gilt balls and a vane on its summit. On holidays

the pole was decorated with flags and garlands. It was removed in 1718,

and sent by Sir Isaac Newton to Wanstead Park to support the largest

telescope

in Europe." (The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, E. Cobham Brewer,

1894) The final coup de grace came when the Victorians revived the maypole

tradition as a "rustic delight". Far from the potent fertility

symbol presiding over drunken men dressed as stags pursuing screaming

maidens,

the poor, emasculated maypole was finally reduced to a pretty prop in

children's

dancing games.