A New School of Anti-White (French)Historical Thinking in Montreal?

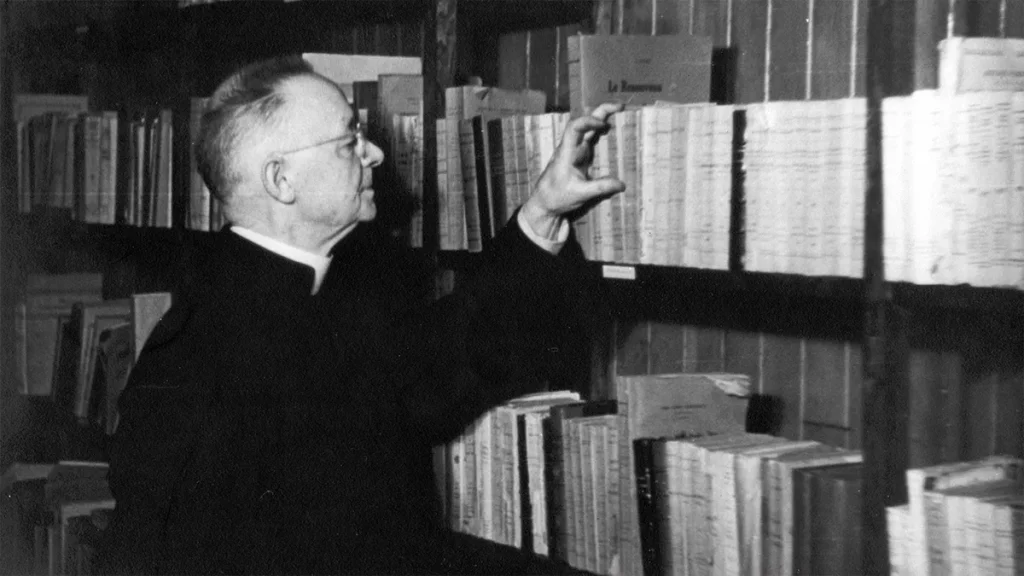

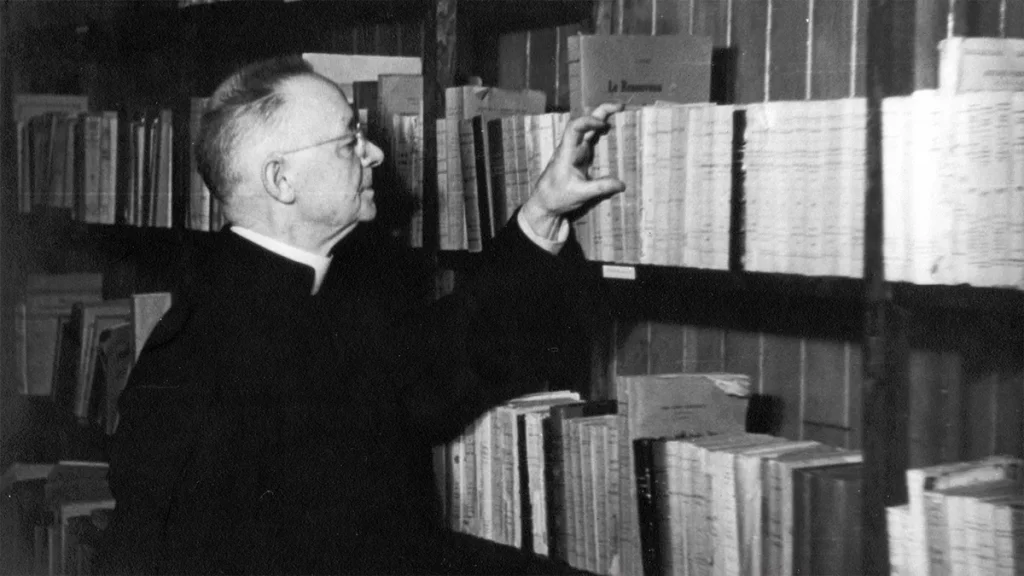

In mid-September 2024, a curious story surfaced in several newspapers: six history professors

at the University of Montreal (UdeM) were attempting to strip the Lionel Groulx Pavilion of its

name. Their reasoning? The esteemed hist

orian and Catholic canon no longer fits the trendy

new dogmas of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Shortly afterward, the

announced it was renaming the Lionel Groulx Prize, citing the words of a

young, self-righteous historian from Montreal.

To the untrained eye, this might seem like a sudden break from tradition. But those paying

attention to the ideological winds blowing through UdeM will know this is merely the latest

chapter in a broader campaign to redefine Quebec’s past. Just a year earlier, in September

2023, the university hosted a conference on colonialism that blurred the lines between academia

and activism. Instead of reasoned historical analysis, attendees were treated to sessions packed

with ideological sermons worthy of a political rally. The event was so overtly militant that even

some Journal de Montréal columnists felt compelled to call it out.

And it didn’t stop there. The same group of activist-scholars has been busy holding lectures filled

with absurd accusations. One memorable claim? That the decolonization theories espoused by

Parti Pris sovereigntists were responsible for “erasing Indigenous peoples” and constitute “a

form of colonial violence still present today in debates like systemic racism.” 1

These academics seem fixated on portraying Quebec’s francophone population as inherently

oppressive. Some dedicate their careers to studying racial issues, but only to paint French

Canadians in the worst possible light. Their arguments are often flimsy and deliberately

inflammatory. One example: blaming the entire Quebec Catholic population for residential

schools simply because they supported the clergy 2 . Using that logic, should taxpayers be held

responsible for every government policy? Should all Muslims be blamed for terrorist attacks

committed by extremists?

Worse still, these historians scour old textbooks and photographs to “prove” that Quebec’s

national identity is rooted in racism. They conclude their work with declarations like, “I must

recognize the privilege of my whiteness and understand how it enables me to deny or ignore the

racist, colonial culture from which I come.” 3 Such statements might sound laughable, but they’re

catnip for a radical left eager to undermine Quebec’s history and culture.

“The Montreal School”,The militant activism of today young historians is so pervasive it may well signal the emergence

of a new school of historical thinking. Quebec has seen several such movements over its history.

The “Montreal School,” led by figures like Michel Brunet, Guy Frégault, and Maurice Séguin,

argued that French Canadians’ social and economic struggles stemmed from the dislocation

caused by the British Conquest. The “Quebec School,” on the other hand, emphasized internal

challenges, such as the Church’s influence. Revisionists eventually moved away from Quebec’s

specificities altogether.

Now, the new UdeM historians seem intent on exposing the supposed flaws of French

Canadians—too white for these apostles of diversity. Every minority group deserves to be

glorified, except, of course, francophones. Pluralism must be exalted, even at the expense of

common good 4 .

But what should we call this new school of thought? Philosopher Roger Scruton, in England and

the Need for Nations, coined the term “oikophobia” to describe the rejection of one’s home andheritage (oikos meaning “home” in Greek). Oikophobes are elites who disdain and denigrate

Western traditions, instinctively favoring foreign cultures. As early as the 2000s, Scruton noted

how oikophobia was spreading through American universities. It’s a fitting label for UdeM’s new

historians.

Some researches have shown a steady decline in university history program enrollment. These

oikophobes are undoubtedly part of the problem. How many young people now turn away from

history because its study has become synonymous with self-loathing and ideological

indoctrination?

Instead of celebrating Quebec’s rich history, these scholars tear it down to align with the latest

academic fads. If we allow this trend to continue unchecked, what kind of future are we building

for the next generation? It’s time for Quebecers to reclaim their heritage and demand a more

balanced, thoughtful approach to understanding the past.

1 Third paragraph in this report of the November 2021 workshop: https://histoireengagee.ca/retour-sur-

latelier-le-colonialisme-dimplantation-au-quebec-un-impense-de-la-recherche-25-26-novembre-20211/

2 See: https://histoireengagee.ca/lhistoire-des-pensionnats-de-louest-est-une-histoire-quebecoise/

3 Catherine Larochelle, School of Racism: A Canadian History, 1830–1915, University of Manitoba Press,

2023.

4 See Catherine Larochelle’s brief as part of the consultations on Bill 64 (An Act to establish the Musée

national de l’histoire du Québec, September 2024).