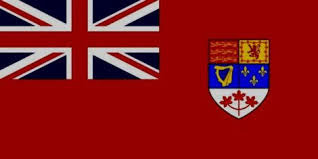

Throne, Altar, Liberty

The Canadian Red Ensign

Thursday, January 15, 2026

Is Orange the new Red?

Do you remember the story of Jacobo Árbenz?

Árbenz was elected the president of Guatemala in 1950 and entered that office early in 1951. His primary policy and the focus of his presidency was agrarian reform. What this meant was that large sections of farmland that were currently not under cultivation were expropriated by the government and handed over to poor farm workers. To Americans this smacked of Communism and certainly there was a resemblance in that the redistribution of wealth was involved. There were also differences in that unlike Communists Árbenz compensated the large landowners whose property he seized and that, unlike in Communism, the seized land did not become communal property but remained private, albeit redistributed to a larger number of owners. Somewhat ironically his program lined up, in desired outcome albeit not in means, with that of the literary group known as the Vanderbilt Agrarians or Twelve Southerners whose 1930 anthology/manifesto I’ll Take My Stand inspired Richard M. Weaver whose 1948 Ideas Have Consequences sparked a renaissance of Burkean thought in the historically liberal United States of America.

Among those for whom the similarities between Árbenz’ version of agrarianism and Communism outweighed the differences was the United Fruit Company which had something of a monopoly on the banana trade in that part of the world – Guatemala was a “banana republic” in the literal sense of the term – and from whom much of the redistributed land was seized. The company lobbied the American government to intervene and plans were drawn up to do so in the last days of the administration of Harry Truman. It was during the presidency of Truman’s successor, however, Dwight Eisenhower, that the Árbenz government was toppled in 1954. Eisenhower’s Secretary of State was John Foster Dulles who had previously been the United Fruit Company’s lawyer. His brother Allen, whom Eisenhower named director of the CIA, oversaw the coup, and also had connections to United Fruit.

Needless to say the Eisenhower administration, especially the Dulles brothers, and United Fruit all portrayed the CIA coup as an action taken to prevent the Communist takeover of Guatemala. Ironically, however, of the two presidents involved in this story, it was Dwight Eisenhower, not Jacobo Árbenz who was most likely an actual Communist.

Robert W. Welch Jr., who after his retirement from his career as America’s Willy Wonka had founded the John Birch Society to combat Communism in 1958, in 1963 privately published a book entitled The Politician. The book, which grew out of a letter that Welch had privately circulated a decade earlier, has remained in print and was given the subtitle “A look at the political forces that propelled Dwight David Eisenhower into the Presidency.” Welch argued that Eisenhower was “a dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy”. Russell Kirk quipped in response “Ike’s not a Communist, he’s a golfer” and quoting this witticism became William F. Buckley Jr.’s stock response to Welch’s allegations. The editor of National Review had broken ties with Welch and the JBS, ostensibly over the book although more likely over the society’s opposition to the Vietnam War. While Kirk had undoubtedly coined a clever phrase, Buckley’s use of it was a way of avoiding having to answer Welch’s actual case against Eisenhower.

Of course, someone could argue that no such answer was necessary because when it comes to allegations the burden of proof is on the accuser and Welch’s evidence fell short of being the definitive proof that, say, a leaked copy of the Communist Party membership roll with Eisenhower’s name on it or the testimony of ex-Communist Party members that he had been active at their meetings, would have been. In McCarthy and his Enemies (1954), however, Buckley and his brother-in-law Brent Bozell had examined the cases of those whom Senator Joseph McCarthy had named and showed that if it could not be proven that each of these was a card-carrying Communist it could at least be demonstrated that there was cause in the vast majority of the cases for flagging the individual as a potential security risk. If Buckley had applied this same standard to Welch’s book, he would have found it less easy to dismiss.

It was not merely that Eisenhower had made a couple of bad decisions here or there that one could argue had in some way or another been to the advantage of the Soviet Union. He had a consistent pattern of acting in ways that primarily benefited the Soviets, a pattern established before his presidency, even before the Cold War itself, in World War II. About a year or so before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (sic), Eisenhower had been brought to the attention of Franklin Delano Roosevelt by his daughter after she had attended a party in which the young officer had filled her ears with gushing, sycophantic, praise of her father. FDR, note, wore his pro-Communism on his sleeve, having been the first American president to recognize the Bolshevik government, having recalled an ambassador who told the truth about conditions in the Soviet Union and replaced him with one who sent back lying reports about the paradise that Stalin was creating and whose equally deceitful memoir became the basis of a vile pro-Stalin propaganda film that FDR ordered made, who believed that he and Stalin had such an affinity that he would be easily able to manipulate the Soviet dictator (the reality was the other way around), and whose bureaucracy was so filled with Communist agents in extremely high positions that had Joseph McCarthy been a senator at the time instead of an air-force tail-gunner and had he made the same allegations he would make during the 1950s and on the same scale, he would have been guilty of grossly underestimating Soviet influence in the American government. FDR’s government advanced Eisenhower through the military ranks far more rapidly than his skill or experience supported. The rate accelerated after the United States entered the war and half a year later he became commanding general of the American army’s European Theater (sic) of Operations. A year and a half later he was named Supreme Allied Commander.

By the time the United States entered the war, Hitler had already broken his pact with Stalin and launched Operation Barbarossa, and so the Soviet Union was now one of the Allies as well. Stalin requested that another front be opened up as soon as possible to relieve the pressure on the Russian army and this was not an unreasonable request under these circumstances. Prior to D-Day, however, there was much argument over where that front should be. Sir Winston Churchill wanted a Mediterranean invasion that would approach Germany through Italy and the Balkans. Eisenhower and his superior, General Marshall, however, backed Stalin’s demand that the second front be opened up in France. The Americans and the Soviets won out in the end, but the success of the Norman invasion does not prove them to have been right. One of the reasons Churchill wanted a Mediterranean front was to prevent, or at least lessen, one of the less pleasant consequences of the Allied victory, namely the fall of Eastern Europe into the hands of the Soviets.

While Eisenhower’s insistence on France in itself does not prove that he wanted Eastern Europe to fall behind what Churchill would soon dub the “Iron Curtain” his subsequent actions did nothing to clear him of the charge. After D-Day, Eisenhower’s “broad front” strategy prevented commanders who wished to move faster and end the war quicker, most notably General Patton, from doing so. In Patton’s case, he cut his fuel supplies in August 1944 and then ordered him to assume a defensive position. If Eisenhower had other motives at the time than slowing the Western Allies so the Soviets could advance from the East this cannot be said of what happened when the fall of Germany was imminent in April 1945. At this point Eisenhower halted the Western Allies at the Elbe River and called up Stalin and told him to take Berlin. While Eisenhower claimed that this is what had been agreed upon prior to the invasion, Churchill disputed this claim. Eisenhower had received requests from German cities that lay in the path of the Red Army asking that they be allowed to surrender to the Americans instead. Eisenhower denied these requests, much like the civilian government of the United States denied the surrender requests that Japan had been sending General Douglas MacArthur for over a year before the United States committed the single greatest atrocity of the war when she dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Meanwhile, discussions were underway as to the next steps to be taken after the war was won. In 1944, a proposal for imposing a Carthaginian peace on Germany was made. It was called the Morgenthau Plan after Henry Morgenthau, Roosevelt’s Secretary of the Treasury under whose name the initial proposal was distributed, although Morgenthau’s assistant, Harry Dexter White was the brain behind it. White, who would later dominate the Bretton Woods Conference that gave birth to the IMF and the World Bank, was identified by both Whittaker Chambers and Elizabeth Bentley as an informant of the Soviet spy rings they had been associated with. These allegations were verified quite early and the post-Cold War publication of the Venona Project findings and the opening of the Soviet archives have established the matter beyond a reasonable doubt. The Morgenthau Plan, if it had been enacted, would have left Western Europe much more vulnerable to Soviet invasion. While Eisenhower would downplay his connection to the Morgenthau Plan later, Welch cited Morgenthau’s former assistant Fred Smith, as identifying Eisenhower, who hosted Morgenthau and White on 7 August, 1944, as having “launched the project.”

Welch also quoted Eisenhower himself, from his memoir Crusade in Europe (which was ghost written for him by Joseph Fels Barnes, an American journalist who had been the American director of the Institute of Pacific Relations, a think-tank that served as a Communist front, and who had been named as a Communist by Whittaker Chambers), as having said at that same meeting “Prominent Nazis, along with certain industrialists, must be tried and punished. Membership in the Gestapo and in the SS should be taken as prima facie evidence of guilt. The General Staff must be broken up, all its archives confiscated, and members suspected of complicity in starting the war or in any war crimes should be tried.” This, was eventually acted out at Nuremberg. At the Tehran Conference, when Stalin and Roosevelt made ghoulish remarks about a post-war “victor’s justice” involving the summary execution of random German officers, Churchill walked out in disgust (it was Stalin, not the American president who went after him and appeased him with the excuse that Solomon put in the mouth of the “mad man who casteth firebrand, arrows, and death”) and after the Nuremberg Trials his son Randolph, speaking in Australia called the executions of the German officers murder and said “They were not hanged for starting the war but for losing it. If we tried the starters, why not put Stalin in the dock?” This was not a popular opinion then and it is less popular now in this day and age in which questioning the received account of the other side’s atrocities in that war is absurdly treated as a crime itself but the Churchills recognized what we have allowed to sink into Orwell’s memory hole, that putting those you have just defeated in war on trial before a newly created court that could not possibly have any legitimate jurisdiction was not in accordance with the principles that, however often they may have been ignored, have informed our civilization’s ideas of law and justice since classical antiquity although it fits quite neatly into the Soviets’ barbarous idea of justice. The American who was most outspoken in expressing this forgotten truth at the time was Senator Robert. A. Taft of Ohio, the son of former American president William Howard Taft. The story of his bravery on this occasion can be found in the final chapter of Profiles in Courage, ghost-written for John F. Kennedy by Ted Sorenson. Senator Taft, incidentally, was Eisenhower’s chief rival for the Republican Party’s nomination in the election that put Eisenhower into the White House.

The most inexcusable of Eisenhower’s war-era pro-Communist activities, however, was his involvement in the forced repatriation of refugees from Communism. This is often called “Operation Keelhaul”, which is the title of the fourth chapter of Welch’s book as well as of the book-length treatment of the matter by Julius Epstein, although as an official designation this name was more limited in scope, applying to a specific set of operations that were carried out for about a year after the war, while the entire program of repatriation to the Soviets began before the war ended and extended, in some cases to as late as 1949. Count Nikolai Tolstoi entitled his excellent book about this matter Victims of Yalta. The whole sordid affair, however, went far beyond what was agreed upon at Yalta and, indeed, began in 1944 before the conference had even taken place. By the time it was over, up to five million ex-patriots of Soviet-occupied territory, including territory that had only just become Soviet-occupied in the war, were turned over to the Red army to face torture, the prison and labour camps administered by GULAG, and death. Nor, as Eisenhower apologists have been known to claim, were these all or even primarily, Russians who had defected to Hitler’s army (in the case of those who did meet this description, American Undersecretary of State Joseph Grew, one of the more responsible negotiators, in the talks leading up to the Yalta agreement pointed out that to meet Stalin’s demands would violate the Geneva Convention which required that these, captured in German uniform, be treated as Germans). They included people from lands that Hitler had captured who had ended up in his camps, from which they were “liberated” only to be surrendered to Stalin. They included soldiers who, individually or as bands, had fought in the war alongside American and other Allied forces, but for all that were turned over to Stalin’s army at his request, by Eisenhower’s orders. They included patriots from the countries that the Red Army overran on Stalin’s march to Berlin who had put up a fight against the Soviet takeover but, before their countries fell, surrendered to the Americans instead only to be turned over the Soviets by order of Eisenhower.

From all of this, which pertains only to Eisenhower’s actions as a military commander and of which I have given merely a small sampling of what Robert Welch provided in the first five chapters of his eighteen chapter book, it should be evident that Buckley’s own standard concerning the Joseph McCarthy allegations as articulated in Buckley’s own book, had been met by Welch with regards to Eisenhower. Indeed, suppose one was trying to prove the opposite of what Welch claimed, trying to demonstrate that Eisenhower was a solid anti-Communist. The evidence is far less abundant, to put it mildly. Eisenhower claimed to be anti-Communist in his run for the American presidency but that took place long after the time when openly hug-a-Red types like FDR could be elected president four times in a row. The Cold War was underway and anyone hoping to win had to present himself as an anti-Communist. Eisenhower basically claimed to be an anti-Communist by association by making Richard Nixon, whose anti-Communist credentials as the investigator in the Alger Hiss case were impeccable, his running-mate. Apart from his association with Nixon, the strongest evidence for Eisenhower’s anti-Communism was his deposing of Árbenz who, as we have seen, was not a real Communist and who was removed for reasons that had nothing to do with real anti-Communism. Outweighing this phony example of Communist-toppling is another example of regime change from the same era. From 1957 to 1959, the Eisenhower administration, including the same Dulles brothers who pushed for the removal of Árbenz pursued a policy of weakening the government of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba and supporting the revolutionaries. Dulles’ CIA even provided training and arms to the revolutionaries. Ezra Taft Benson, leader of the heretical Mormon sect and Eisenhower’s Agricultural Secretary, tried to persuade the Eisenhower administration to abandon its support for the revolutionaries and the deaf ears he kept encountering eventually persuaded him of the truth of Welch’s thesis. In 1959 the revolutionaries, led by Fidel Castro, came to power and declared their allegiance to the Soviet Union. For a book length account of the American government’s responsibility for this outcome see The Fourth Floor: An Account of the Castro Communist Revolution, the memoir of Earl E. T. Smith, who was the American ambassador to Cuba during the period of the revolution.

On 3 January, the American air force bombed Venezuela while a team of American agents infiltrated the country, captured its president Nicolás Maduro and his wife, and removed them from Caracas to New York where they were charged with various crimes having to do with narcoterrorism. When I heard the news, Guatemala in 1954 came immediately to mind.

In both incidents, the American government removed the president of a Latin American country. Both times they justified their actions by accusing the removed president of the greatest evils of the day – Communism in the case of Árbenz, narcoterrorism in the case of Maduro, although defenders of the American government’s actions also frequently call Maduro a Communist. In the case of Guatemala the American government’s real motivation was the economic interests of United Fruit. In the case of Venezuela, it was, as the American president openly admits, all about the country’s oil which had been nationalized by Maduro’s predecessor. In both cases, the American president was himself likely a Communist.

In 1987, Donald Trump visited the Soviet Union, ostensibly to make a deal to build a hotel in Moscow. Alnar Mussayev, a Kazakhstan politician who served in the KGB during the 1980s, claimed last year that Trump had been recruited as an asset by the KGB during this visit and given the codename “Krasnov”. While Trump’s political opponents, the Democrat Left, have been accusing him of being a Russian puppet for years, Mussayev’s claim is somewhat different. When Hilary Clinton, et al., accused Trump of being controlled by Russia, they were thinking of Russia as a nation, a post-Communist country which, in their eyes, had gone down a dark path since the break-up of the Soviet Union. The KGB, however, was not merely a Russian national agency, but a Communist agency.

It is 2026 now and the Soviet Union has supposedly been gone for thirty-five years. I stress the word “supposedly.” In his 1995 book The Perestroika Deception, Anatoliy Golitsyn warned that the breakup of the Soviet Union was a façade intended to lull the West to sleep as a late stage in a long-term Communist strategy of deception thought up decades earlier. The Communist Party and its KGB enforcers remained firmly in charge, Golitsyn argued. As crazy as this may have sounded, the credibility of the book was greatly enhanced by Golitsyn’s earlier, 1984, New Lies for Old, which also warned of a long-term strategy of deception thought up by the Communists in the late 1950s. This book contained many predictions, most of which were fulfilled by the early 1990s.

The president of Russia, Vladimir Putin, had been a career KGB agent before the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 and his entry into politics. That he has been in charge of Russia, alternating as prime minister and president, for the past quarter century, adds further credibility to Golitsyn’s claim that the KGB, and the Communist Party behind it, remained in power after the supposed Soviet breakup. If Mussayev is right about Trump, then Communism once again has an agent in the White House, as it did at the time Golitsyn says the Communists agreed upon this strategy. The difference is that at that time, Communism was regarded as a serious threat, today it is regarded as a thing of the past, a defeated foe, making a Communist agent in the White House that much more of a threat.

Of course, even if Mussayev was talking out of his rear end and Trump is not a KGB chess piece in a game the Communists have been playing since the 1950s, he is still the world’s biggest jerk. This is another thing common to him and Eisenhower. Suppose Welch’s interpretation of Eisenhower’s actions was as off-base as Buckley and Kirk claimed it was. He still ordered the forced repatriations to the Soviet Union. He still supported the revolution that put Castro into power. Communist or not, he was a real bastard.

Maduro may very well be as bad as Trump’s zombie cheerleaders claim him to be. Indeed, I’d be surprised to hear that he wasn’t. That does not make the Trump administration’s actions right. The United States does not have some kind of universal jurisdiction to act as policeman, prosecutor, judge and executioner for the entire world. Nor should her acting like she does be tolerated by the rest of the world.

One of Krasnov’s predecessors, John Quincy Adams, while serving as James Monroe’s Secretary of State, famously declared “America does not go abroad, in search of monsters to destroy.” While Adams’ idea of a United States that minded her own business rather than everyone else’s was not absolute – it was not until a couple of decades later that he repudiated his belief in the repugnant doctrine of Manifest Destiny, i.e., America’s supposed destiny to subjugate everyone else in this hemisphere to the rule of the United States, and then, for reasons other than that he perceived the inconsistency between this and his nobler idea of a United States that minded her own business – it remained influential into the first half of the twentieth century. World War II was believed to have killed it, nailed its coffin shut, and buried it. Adams’ words, however, were revived after the end of the Cold War by those who thought that the United States should roll back her military presence throughout the world and who rejected George H. W. Bush’s vision of a “New World Order”, announced in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, in which the United States would lead a coalition of nations in policing the world against actions such as Hussein’s.

These were generally those on what passes as the Right in the United States – the United States having been founded on the ideology of liberalism by deists who rejected everything the real Right stood for, i.e., royal monarchy, an established Church, and the rest of the institutions and order of pre-liberal Christendom – who dissented from the neoconservatism that had come to dominate the American Right by the end of the Cold War. A note to readers from my own country, while we use “neoconservative” to refer to Canadian “conservatives” who define their “conservatism” in American terms rather than those of the more authentic Toryism of our own country and the larger British Commonwealth, in the United States “neoconservative” refers to a group of pundits, who had been part of the New York Intellectuals in the period leading from the war into the second half of the twentieth century and as such had been on the Left with views ranging from those of FDR type New Dealers to Trotskyism, who in response to the development of the anti-Israel, pro-Palestinian New Left in the 1960s and 1970s, realigned themselves with the American Right. This American neoconservatism blended what was basically a Manichean view of the world as a battleground between the forces of Good and a reified Evil with a Nietzschean view of “might makes right.” Practically, however, its ideas were that the rest of the world was entitled to American liberal democracy, that the United States had the duty to provide the rest of the world with American liberal democracy, whether they wanted it or not, even if it took all of America’s bombs and bullets and boots on the ground to do so, and especially if it meant regime change in a country whose government Israel wanted removed. This belligerent and ignorant hawkishness became even more pronounced as American neoconservatism entered its second and third generations. Those who quoted John Quincy Adams in response to the neoconservative takeover of the American Right were called paleoconservatives (Pat Buchanan, Sam Francis, Thomas Fleming, Paul Craig Roberts, Paul Gottfried, et al.,) and paleolibertarians (Murray Rothbard, Lew Rockwell, Ron Paul, et. al.,) and when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States the first time this was widely regarded as a victory for them and a defeat for the neoconservatives who generally opposed Trump.

In Donald Trump’s third bid for the American presidency in 2024, however, he had the support of these same neoconservatives. This, as became evident before Trump was even inaugurated the second time, signalled that The Apprentice, White House Edition, 2.0 would be very different from the original and not in any way that could be described as an improvement. In the new iteration Trump has been acting as if he were elected president of the world rather than merely of one country and that the rest of the world has to bow to his wishes or be forced to do so either by his preferred means of economic force, such as tariffs, or if necessary by more conventional military means. The only county he does not seem to think he has the right to boss around is Israel, the very country the American neoconservatives place at the top of their pecking order above their own.

Let us now return to the thesis I have been suggesting in this essay. It was never very likely that the Communist Party would achieve its goal of world-wide Communism by means of the Soviet military. The establishment of a world-wide Pax Americana under the United States as the sole superpower, however, was a likely outcome of the Cold War and it might serve Communism’s end better than the Red Army ever could if the break-up of the Soviet Union was the elaborate ruse Golitsyn painted it to be and if a KGB agent recruited in the perestroika and glasnost phase of the Communist strategy were to become the American president as it entered its end game. Should someone raise the objection that it makes no sense for an extremely wealthy businessman like Donald Trump to be a Communist agent, I would answer that such an objection displays ignorance of the history of Communism. From 1848 when wealthy cotton merchant Friedrich Engels co-wrote the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx to 1917 when the Bolshevik Revolution was financed by German and American bankers (see Anthony C. Sutton’s Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution) to the very end of the Cold War it was always capitalist money that kept Communism afloat. Has not the open policy of the People’s Republic of China for decades been to finance Communism with capitalism?

We have become too used to thinking of Communism and capitalism in terms of the Cold War paradigm which portrayed them as enemies that are each the polar opposite of the other. In such a paradigm it would be difficult to explain the thinking of the American president just prior to the Cold War. What made FDR so naïve when it came to Stalin? It was his conviction that despite the differences in state structure and economy, the United States and the Soviet Union were ultimately on the same side and not just in the sense that they were both at war with the Third Reich but in the sense that they were both Modern countries to whom the future belonged as opposed to older powers whose day had passed into which category he placed the other Allied powers.

From the perspective of those of us who are still Tories, who still cherish what the original Right stood for, who still believe in kings, orthodox Christianity, the Church, roots, tradition, honour, loyalty, chivalry and all the old pre-mercantile virtues, FDR’s point of view was in a sense more correct than that of the Cold War paradigm. This correctness did not lie in its more positive assessment of Stalin and Communism, but in its identifying the Modern spirit of progress that united the USA and USSR as outweighing the differences between their economic models. We, however, would say that what FDR celebrated, we decry because this Modern spirit has been the enemy of all we hold dear for centuries. Communism is more open and upfront about this hostility, being officially atheist rather than merely officially secular, but this arguably makes capitalism the more dangerous of the two. Capitalism is better as an economic model because it is not based on calling what is protected as a good by God’s Law, property, an evil, like Communism is, but both systems openly worship and serve Mammon.

Trump’s critics on the Left typically liken him to Hitler. Of course they have been doing this all along and they do this to everybody. The comparison, therefore, had more weight to it when it was made this week by podcaster Joe Rogan. The thing about Hitler is, while most contemporary thought likes to imagine that it was Nazi distinctives, things which set Nazism apart from other systems like Communism, that made it so bad, the reality is that it is the much larger group of areas in which Nazism was indistinguishable from Communism – a totalitarian state that governed by fear enforced by secret police and prison camps, etc. – that made it so bad, which is something Sir Winston Churchill certainly understood. Rogan compared ICE, the immigration enforcement agency of the Department of Homeland Security, to the Gestapo. He could have added the Cheka, the NKVD, or any other of the various incarnations of the Soviet secret police. The comparison is quite valid. An organization empowered to hide behind masks, stop individuals in their daily lives and demand to see their papers is behaving exactly like these Communist agencies. Granting an agency powers of this sort seems to be more designed to harass and intimidate American citizens than to deal with the very real immigration problem the United States, like other Western countries, faces. It was George W. Bush rather than Trump who created ICE, but the sort of disregard for the rule of law and reasonable limitations on powers that Rogan was commenting on is increasingly characterising the second administration of the man who only a few days ago told an interviewer that his own morality was the only limit on his power.

From a sound Tory perspective, it is not that this sort of thing has finally come about in the United States that is surprising so much as that it took so long for it to happen. The American Revolution was based on the same toxic notions that Edmund Burke rightly referred to as “armed doctrines” when they were shortly thereafter re-used to produce the French Revolution which very quickly brought about the Reign of Terror. T. S. Eliot wrote in 1939 “If you will not have God (and He is a jealous God) you should pay your respects to Hitler or Stalin.” Today they will have to make do with Krasnov the Orange. — Gerry T. Neal