Slavery apology added to the list

Let’s be quite clear. The only slavery since Canada became and independent Dominion in 1867 was on the part of West Coast Indians owning other Indians as slaves well into the 19th Century. In 1794, Sir John Graves Simcoe abolished slavery in the forming British colony of Upper Canada. This was 40 years before the mother country would abolish slavery throughout the British Empire in 1834.

Writing in the National Post (June 13, 2025) N.W. Liston recounted : “Jody Wilson-Raybould’s father describes the pride he felt in 1951, sitting on his grandfather’s knee as he was served by his slaves. Indigenous produced programs on APTN have begun noting the power the Haida (who ranged as far as northern California on raids) possessed when Haida Gwai’s population was 25% slave. One recent episode on local tribal wars reconstructs memorable battles such as the luring of a large (1000?) raiding party into Maple Bay near Duncan, where a 3 sided trap was sprung from land and water, the slaughter turning the water of the bay red. The victorious alliance, fed up with constant raiding, then finalized the solution by “marrying” the wives of the dead. Surprisingly, “Blood in the Water” the estimated date of this battle of around 1850.

Reconciliation can only take place between real peoples, not the distorted, grotesque caricatures produced by both ignorance and design. Understanding the “other” does not come from projecting your own stereotypical image in the absence of actual experience, but formed bit by bit from real encounters with real people and attempts to see the world from another’s point of view, not assuming theirs is the same as yours. Ghosts are not your friends.”

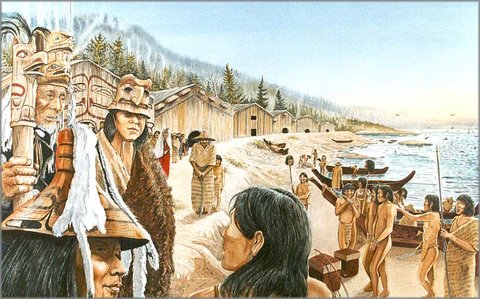

West Coast slaves — Indians owned by other Indians!

Negro slavery? We never did it. It was abolished 73 years before we even became a Dominion. No apology. No way! No more White Guilt.

An additional acknowledgment

- National Post

- 13 Nov 2025

Just as Indigenous land acknowledgments become a ubiquitous aspect of Canadian life, activists are attempting to normalize a second acknowledgment that would similarly precede every single speech, meeting or public event in the country.

This was on view at the City of Toronto’s official Remembrance Day ceremony at Toronto City Hall.

After a standard land acknowledgment mentioning the various First Nations whose traditional territories overlap with the City of Toronto, attendees were also asked to acknowledge “those who were brought here involuntarily; particularly those brought to these lands as a result of the TransAtlantic slave trade and slavery.”

While Toronto does indeed sit atop land that used to be Indigenous, the historical claims in the slavery acknowledgment are less accurate.

As outlined in a recent report for the Aristotle Foundation, African slavery was never a defining feature of Canada, particularly as compared to the United States.

The generally accepted view of historians is that, over 200 years, a total of 7,000 African slaves were owned in the French and English colonies that would eventually form Canada.

In contrast to the U.S., Canada’s contemporary Black population is comprised mostly of people who trace their lineage through Caribbean immigrants, or freed U.S. slaves who settled in Canada.

What’s more, Canada became one of the first jurisdictions on earth with an explicit sanction against human bondage. The 1793 Act Against Slavery, passed by the colonial legislature of Upper Canada, would end up representing the British Empire’s legislative first step toward its ultimate ban on slavery in 1834; 33 years before Confederation.

As noted by the Aristotle Foundation, the much more prevalent form of slavery in pre-confederation Canada was the version practised by Indigenous societies — iterations of which could be found on the West Coast well into the 19th century.

Nevertheless, the City of Toronto is one of several Canadian institutions that is still attempting to normalize a “slavery acknowledgment” in addition to standard Indigenous land acknowledgments.

Starting in 2018, the city codified the text of an “African Ancestral Acknowledgement” that was to be used to open public events, provided it was “delivered by a person of African descent.”

If no such person could be found, a non-black person is instructed to pre-empt the acknowledgment with the line “though I am not a person of African descent, I am committed to continually acting in support of and in solidarity with Black communities seeking freedom and reparative justice in light of the history and ongoing legacy of slavery that continues to impact Black communities in Canada.”

Similar acknowledgments can also be found in various Toronto non-profits and government agencies.

The Toronto Seniors Housing Corporation, for one, has a section on its website devoted to acknowledging slavery, even while noting that said slavery usually didn’t happen in Canada. “We acknowledge the experiences of Black peoples who arrived in Canada seeking a better life following the abolition of slavery by the British in 1834, while also recognizing the structural, systemic, and individual racism that they encountered,” it reads.

Nova Scotia, long a centre of Canadian Black life due to its large pre-confederation communities of freed slaves, has also seen several institutions flirting with slavery acknowledgments.

The officially recommended land acknowledgment provided by the Nova Scotia chapter of CUPE, for instance, mentions the forcible displacement and enslavement of people of African descent,” adding “much of the privilege many of us have in this space stems from colonialism in the past and today, and in the oppression of Black & African Nova Scotian people.”

Dalhousie University has drafted an official African land acknowledgment stating that “African Nova Scotians are a distinct people whose histories, legacies and contributions have enriched that part of Mi’kma’ki known as Nova Scotia for over 400 years.”

While land acknowledgments are now standard practice across Canadian legislative session, city hall meetings, church services, airline flights and even hockey games, they’ve notably never taken hold in the United States outside of the occasional corporate boardroom or academic gathering.

In a January op-ed for The New York Times, Indigenous history professor Kathleen Duval said that even this scattered usage had outlived its usefulness. Wrote Duval, “they’ve begun to sound more like rote obligations, and Indigenous scholars tell me there can be tricky politics involved with naming who lived on what land and who their descendants are.”

Canadian views are more sanguine. Polls show that Canadians generally welcome land acknowledgments as a gesture of Indigenous reconciliation, even if they object to notions that they live on “stolen” land. A June survey by the Association for Canadian Studies found that 52 per cent of Canadians rejected the assertion that they lived on stolen Indigenous land.