by Ricardo Duchesne

Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV | Part V | Part VI | Part VII | Part VIII

|

| Life in the 1940s |

Canada had strong collective ethnic markers before WWII/1960s, with immigration policies that excluded ethnic groupings deemed to be an existential threat to the “national character.” But as a liberal nation, Canada had a weak sense of the political, a weak understanding of the actual way the nation was founded, by a people with a strong Anglo-Quebecois identity rooted in a territory set up against potential enemy groupings. Instead, Canadian leaders imagined their nation to be a contractual creation by individuals seeking security, comfort and liberty. This is why they were highly susceptible to the new normative climate that emerged after WWII.

This normative climate, as explained in Part 1, consisted of four key claims:

- the idea that Western nations should be based on civic values alone, pure liberal rights, rather than any form of ethnic identity prioritizing one ethnic group over another in the nation’s character,

- the notion that races are not real and that it would make no difference, accordingly, to populate Western nations with multiples races,

- romanticizing Third World peoples as victimized humans in need of Western sympathy and promotion, and

- the idea that Western liberal rights, if they are to be truly liberal, must be extended to all humans regardless of nationality.

These claims had been articulated by intellectuals before WWII, but it was only after this war that they took a firm hold over Western civilization.

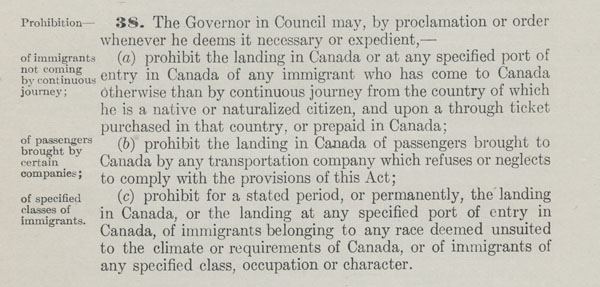

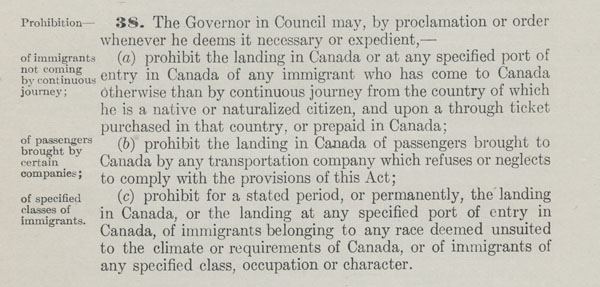

Immigration Act of 1910: White Man’s Country

The ethnically-oriented normative liberalism that prevailed in Canada before WWII was clearly embodied in the Immigration Act of 1910, the Immigration Act Amendment of 1919, and the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923. The norms contained in these acts, even as they came under heavy critical scrutiny after WWII, and confidence in their validity was weakened, prevailed in Canada until the 1962/67 Immigration Regulations, which eliminated selection of immigrants based on racial criteria.

|

| Immigration Act 1910 |

These Acts envisioned Canada as a “white man’s country.” The Immigration Act of 1910 reinforced the immigration restrictions based on race contained in the Immigration Act of 1906, and in all prior government statements and policies about immigration since Confederation. The 1910 Act gave Cabinet the right to enact regulations to prohibit immigrants “belonging to any race deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada or immigrants of any specified class, occupation, or character.”

The Immigration Act Amendment of 1919 introduced further restrictive regulations in reaction to the economic downturn after WWI and the rising anti-foreign sentiments of Canadians after this war. Immigrants from enemy alien countries were denied entry as well as immigrants of any nationality, race, occupation and class with “peculiar customs, habits, modes of life and methods of holding property.” The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 imposed further restrictions on Chinese immigrants to the point that the only Chinese admissible in Canada were diplomats, government representatives, merchants, and children born in Canada who wished to return after leaving for educational purposes. An estimated 15 Chinese immigrants only were able to gain entry into Canada between 1923 and 1946.

Now, while a few million immigrants from Continental Europe had been welcomed to Canada as “agriculturalists” in the nineteenth century, there was considerable ambivalence among the mainstream British elite as to whether non-British immigrant wage workers would fit into the Anglo culture or whether they would be inclined to establish their ethnic ghettos. But with businesses keen on maintaining a supply of cheap immigrant workers, the government came to accept immigrant wage workers from Eastern and Southern Europe, so long as they were subject to assimilation and transformed into English-speakers with manners and habits in line with Canada’s “Britishness.” The expectation was not that non-British Europeans would readily assimilate to British ways, but that they would at least contribute to the economy and become law-abiding English-speaking citizens.

In the 1940s the dominant British in Canada saw themselves as the true representatives of Canadian culture. “Britishness” still remained intrinsic to Canada’s identity. The old imperial heritage, the monarchy, the parliamentary system, the deference to law and order and many other cultural trappings, mannerisms, clothing, and customs were still the standard of what it meant to be “Canadian.” Non-British Europeans were not perceived as members of this British club, but neither were they seen as a threat to the basic functional requirements of Canada. By the 1960s many British Canadians were sympathetic to the presence of other Europeans. Only non-Europeans were identified as “unassimilable races” that would pose a threat, in large numbers, to the unity and cohesion of Canada’s national character and economy viability.

The experience of WWII would result in a total break with these pro-European racial norms and Canadian Britishness. As each generation after WWII would go on to enact ever more radical policies in order to bring these norms to actualization, Canadian liberals would forget that their British-European identity, in contradistinction to non-European modes of being, was their one political concept holding their liberal nation together. Once this last bastion of collectivism was degraded, Canadian leaders would be caught up within a spiral of radicalization unable to decide which racial groups might be their friends and which might be their enemies, which groups might be already lurking within and outside the nation ready to play up the political with open reigns, ready to promote their own ethnic interests under the cover of the universal language of the new norms.

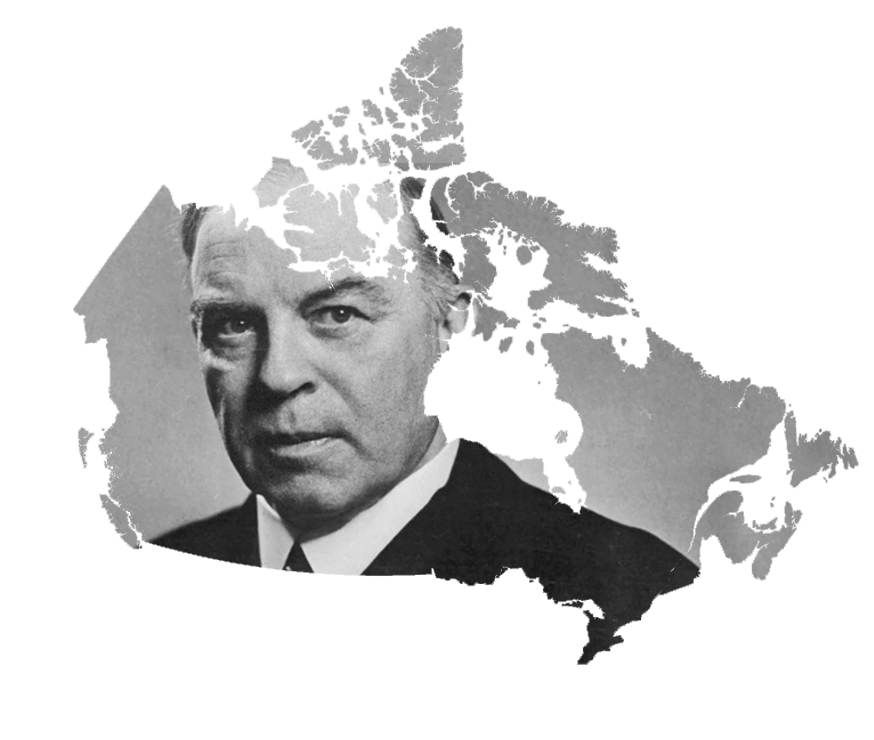

Mackenzie King’s 1947 Speech and New Normative Pressures

|

| Mackenzie King welcomed by CBC |

The take off of the spiral was already evident in a speech that Prime Minister Mackenzie King gave before Parliament on May 1947:

The policy of the government is to foster the growth of the population of Canada by the encouragement of immigration. The government will seek by legislation, regulation and vigorous administration, to ensure the careful selection and permanent settlement of such numbers of immigrants as can advantageously be absorbed in our national economy… With regard to the selection of immigrants, much has been said about discrimination. I wish to make quite clear that Canada is perfectly within her rights in selecting the persons whom we regard as desirable future citizens. It is not a “fundamental human right” of any alien to enter Canada. It is a privilege. It is a matter of domestic policy… There will, I am sure, be general agreement with the view that the people of Canada do not wish, as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large-scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population. Any considerable Oriental immigration would, moreover, be certain to give rise to social and economic problems of a character that might lead to serious difficulties in the field of international relations.

Reading this speech from today’s radicalized situation, the speech seems very strong in its racial orientation, but the discrediting of racial identity is already evident, never mind notions of racial hierarchy. The word “race” is absent from this famous speech, and there is nothing about “Asiatics” being “unsuitable” or being “an alien race,” and not an inkling about Canada “being a white man’s country,” never mind anything about the rightful duty of English peoples to “rule over less civilized races.” These phrases were common in the pre-WWII period. King’s justification for not making any major alterations in Canada’s immigration policies was that it was within the sovereign right of the Canadian government to select “the persons whom [it] regards as desirable future citizens.”

However, while he is aware of the ideology of human rights, he still holds on to the norm that “it is not a ‘fundamental human right’ of any alien to enter Canada… It is a matter of domestic policy.” He adds that “large scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population.” The Canadian government had a right to affirm its national cultural interests rather than submit to extra-national human rights norms.

Yet the spiral could not be appeased. Pressure soon began to mount over the actually existing, racially-oriented, immigration acts of Canada. In the same year of 1947, the minister of external affairs suggested that the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, could not be justified “under the UN Charter which Canada had signed and which called for an end to discrimination based on race, religion, and sex.” Diplomatic pressure from the Chinese government then led the Canadian government, in the same year, to terminate this Act. Moreover, the province of BC, in 1947, gave Asians the right to vote in federal elections and to enter professions from which they had been hitherto discriminated from entering; and in 1949 the federal government also gave Japanese Canadians the right to vote in federal elections.

The issue is not whether we disagree or not with these policies. It is to identify the take off point of the spiral, and how fair minded it all seemed at first. No one in these days was calling for the total diversification of Canada through mass immigration in a state of hostility against the founding Eurocanadians.

It is worth noting that Canada at this time was caving in to pressure from foreign countries and the UN generally, which was made up mostly of non-Western countries without any individual rights but with a strong concept of collective political identity, and, therefore, undisturbed by any norms expecting them to give up their sovereign right to determine the racial character of their nations, even though they, too, were signatories of the UN Charter. Canada, having played an important role in the creation of the UN in 1945, and in the creation of a multi-racial Commonwealth following the granting of independence to India, Pakistan, and Burma in 1947-48, felt morally obligated to the new anti-racist and pro-Third World norms.

The pressure to abide by the new norms was also coming from domestic groups in Canada with a weak sense of the political, business groups believing that what matters in human life is economic growth and prosperity and that liberal nations are places in which abstract individuals enjoy the right to economic liberty and the pursuit of affluence regardless of their collective ethnic identity. It was also coming from leftist liberals who felt that Canada was not living up to its ideals of individual freedom and equality under the law and elimination of any form of discrimination based on non-economic, racial and sexual criteria.

In a Standing Committee of the Senate on Immigration and Labour, which was active from 1946 through to 1953, and which went about collecting the views of multiple groups, ethnic lobby groups, civil servants, organized labour, humanitarian organizations and churches, it was recommended that the Immigration Act of 1910 be revised. The influence of organized labour was felt in this recommendation in its expression that immigration numbers should take into account level of unemployment and the ability of the economy to absorb new immigrants without threatening wages. However, the Canadian Congress of Labour openly recommended an end to racial criteria in immigration policy: “‘race’ ought not to be considered at all.”

Still, the Standing Committee at large, while concluding that racial wording should be avoided in a new immigration act, voiced approval of “Canada’s traditional pattern of immigration and her strong European orientation.” A most interesting statement of this Committee was its assertion that Canada was a nation based on a mixture of white European peoples, not just Anglo-French, but Italians, Greeks, Slavs, Jews, Ukrainians. All these ethnic groups were deemed to be assimilable “into the national life of Canada.” The consensus around these years, then, was that

- Canada would not discriminate against non-Whites who were already citizens in Canada,

- would avoid using racial language in its immigration act, but

- would nevertheless affirm the British-European national character of the nation and its wish to maintain this character.

The spiral, however, was just beginning to gather momentum.